Preface to Longer on the Inside: Very Short Fictions of Infinitely Human Lives

- Colin Fleming

- Jun 7, 2022

- 8 min read

Tuesday 6/7/22

A Few Thoughts on the Physics of Words and Us

Length is one of those concepts with which we all think we’re familiar, until we give it further thought.

Suffering from an irregular heartbeat at an earlier part of my life, I visited a cardiologist who asked if I had trouble walking. I answered that I walked up to thirty miles on some days, and I figured I was okay, but it wasn’t that I was burning up the pavement with my pace. He responded by saying that he meant in terms of when I covered the distance of a block, and being out of breath upon walking one.

“People with heart issues will have problems of that nature,” he told me.

I’d given little thoughts to blocks on my walks, save that there might be a Dunkin’ Donuts in three blocks, and some refreshment—or ambulation fuel—could be at hand, but that exchange gave me cause to rethink what I thought I knew about something so ostensibly simple as a block in a city. Eventually my heart problems were resolved, but every time I’ve been walking since, I’ve imagined what it’d be like to be a future version of myself and have to contend with a block I can barely manage, some fifty yards or whatever it is, that becomes a defining impasse of the struggle to bear.

I think a lot about length as a writer, because I believe I have a different relationship with it. For a long time, I’d compose my stories and people would suggest a word count, having read the story, in that manner in which statements of length casually slip out.

“And it’s only, what, 1000 words or so?” someone might say, when the story in question was closer to 5000. Or the work of fiction that came in at 750 formal words was tabbed as somewhere in the neighborhood of 3000.

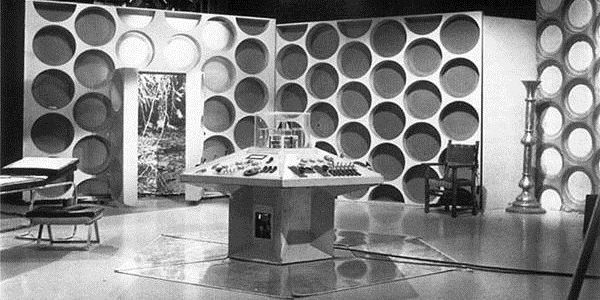

I say “formal words,” because I don’t believe in word counts for myself, in a way. The idea was arresting, intriguing to me, and I began to think of something like Doctor Who and the Tardis. You go back to the earliest episodes from 1963, and a staple of the show is the wonder people express when they discover that the Doctor’s ship is bigger on the inside than the outside. It’s a neat gambit, and you never really tire of it, in all of the iterations of the program and the subsequent Doctors, and I started to think about how are lives work in a similar way.

There’s a fascinating duality to time, in that time owns us, in a manner of speaking. It’s relentless, more so than anything else. More than death, a device—of life, paradoxically enough—that we might regards as being in time’s employ. Outside of ourselves, in the world, there is only so much we can do in a day. We may be able to be both in Montreal and Sri Lanka on a Wednesday, but we can’t also take in a hockey game in San Jose, stroll MoMa in Manhattan, and lead a team of sled dogs across a polar plain in Antarctica.

Time is like, “Not on my watch, laddie,” the time that I imagine being fond of jokes infused with puns that take some starch out of its own grandiose inevitability. Time never lets up, it never slips, falters, pauses for a single breath. It’s indomitable, impressive, daunting, and if you respect it, perhaps you’ll find it inspiring. We can seek to be our own version of time, in the lives we live.

What I’ve learned as an evolving human and writer, though—really the same thing, if you’re maxing out on both—is that we’re in all of these parts of time at once, especially if—and this is the twist—we’re fully present in the time and place we’re at.

Let’s say you have this huge decision to make. It’s going to change how you live, where you live, with whom you live. Alter a relationship. Where are you? Could be a booth at the Burger King. Prosaic. But not for you, is it? This is all playing out in the real-time of your answer. Call it your final answer.

So it’s, what, ten seconds? You’re in the present, obviously. This is happening now. You’re also in your past. You’re thinking about other choices you’ve made, why you made them. Their success or lack thereof. You’re comparing the stakes of this moment to the stakes of other moments. You’re in your future, too, insofar as you’re envisioning it. When we envision, we situate ourselves somewhere else. Empathy, fundamentally, is a form of situating. We get out of our lives, and into someone else. We will ourselves there. We use our imaginations. We do the same thing when we make a decision. The whole of a person—all of their years, their experiences—can be in that moment of answering and making the formal decision. There are ten seconds on the outside, but how many within? It’s longer, isn’t it? It’s a lot longer.

And that’s how we are. It seems to me that if that’s how we are, there ought to be a form of literature that reflects this, and I don’t believe, to date, that there has been. In writing programs, you get what is called microfiction or the short-short. These pieces are always the same. They’re a gloss. A glancing. A snapshot of one moment—if even that—which is supposed to be loaded with depth because of…symbolism? There’s no action. There’s no beginning, middle, end. No arc. No change. People change in our best stories, right? I’m not saying they have to be paragons of growth, but what mettle they have is tested, challenged, called to action, and the response, or the associative contrast, shows us that person in a different way. May show themselves to themselves in a different way. And here’s the biggest thing of all, the kicker, the entire point of fiction, the secret to be let out of the dusty, cloth travel-bag: it shows us to us in a different way.

Ironically, these short-shorts, despite their brevity of word count, do an awful lot of description for description’s sake. Again, I think it’s supposed to help with the would-be Deep Thoughts vibe, but it’s lazy, and it’s so hard to reveal human life and nature and character in an economy of words. Or in any amount of words. So writers cheat and do a form of writerly praying. Ever see a horror movie that has no direction, doesn’t know what it wants to be, isn’t working with much, and what does it do? It gets vaguer and vaguer, pretending that it’s brilliant and this is how meaning must be revealed, and you’re a peon if you don’t get that. You’re not. It’s a copout. It’s bullshit. It’s a con we generally don’t question, for fear—actual fear—that someone will find us lacking. Same thing with the short-short, which are only read by people in those programs anyway. What’s the point?

Think about your own life. Have their not been significant times—defining times—that you can reduce the whole to in order to better see, paradoxically, the whole? In sports, we talk about the key plays of the game. Our lives have key plays. Those key plays exist in connection with the “regular” plays. That contrast makes them what they are. They’re not more valid as representatives of our lives, but their influence is profound. The truth is, in the space of those ten seconds, we live what would ordinarily be rendered—if one was to render it—in a novel. That moment is a flashpoint, but it’s not a greatest hit, if you will. It’s a moment we focus on, that our memory later sticks upon. It meant a great deal to us. Think about the centrality of that importance. It needs no further justification.

But what’s a novel? It’s a term for breadth, more or less. We see it used to make a point of duration. “Your dating profile is a novel!” Well, it’s 200 words, but sure, let’s go with novel. On those same dating sites, someone’s entire profile will read, “I’m to (sic) complicated to be described in words.” They’ve just captured their entirety, though. Now, they don’t know it, and you don’t say it to them, lest you’re courting a mid-day brouhaha, but that’s really all you need to know. It’s an everything, just like we think a novel might be an everything.

It occurred to me—by which I mean, struck through my core as if incised in lightning after years of working, developing, overhauling, evolving as a person and artist—that you could have a work that was, say, 600 words, that contained more than a novel, that was not a short-short nor a vignette, with the whole of lives, with a beginning middle, end, change, arcs, that was not some parable or fairy tale, but what?

I didn’t need a term. “New” would do. “Fitting.” Longer on the inside—like us. I believe the best books are for us—rendered in service to us, I mean—because they’re most like us, and that can involve showing us to us. I think it has to involve it, actually. These books have to be longer on the inside, because we are longer on the inside. Word count and stipulations thereof? You might as well tell me that my soul weighs 11.6 grams.

These were not works I could have written ten years ago. I had to get here. It’s like being a scientist in the lab. You have that “crack open the sky” moment where the light comes in, and you realize what you can do with the structure, and with time itself, partially because you realize what time—inside time, and outside time—is already doing.

Then you get it, and you do it. Then you do more of it. You need to provide instant familiarity. People have to feel like they know the characters from the jump and have known them since before that story started. We are not doing show. We are not doing tell. We are not doing “show, don’t tell,” as they say in writing programs. We are doing is. All words are equally precious because they’re bound in a purpose. We are so here, but we’re also there, and from where and to when, in one human-soaked palimpsest.

It’d be hard for me to overstate how little labels mean to me. This book is their born, bold despoiler. But we all know when something is new, and when it isn’t. Just like we all recognize that the length of who we are—our various forms of duration and distance in our personness—aren’t mappable by external means, so why should they be tethered to our expectations with words?

These words themselves are longer on their insides. It’s the chief quality of substance, or the inner workings, I should say. This is a book of those workings, for eyeballs—whatever their measurable width—out in the world. The time it takes to read them there is not the same as the time it takes to read them on the inside. We all have places to go and things to do, but it’s the inside time—and dimensions—that matter. It’s why clocks—and most non-Who-vian spaceships—are built the way they are, and why we are built the way we are.

So: consider that our countdown to blastoff. But remember: we’re always blasting in to a place where the pitch of play is not like any field one will encounter on the car trip of three miles to the former school of twenty-two years ago where the children of six and eight, respectively, now kick the ball as you once kicked the ball. I offer you this book as a new kind of vessel. In we go. The objects in the mirror are the right size.

Comments