This is an op-ed that no one will run (1)

- Aug 26, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 22, 2025

Wednesday 8/26/20

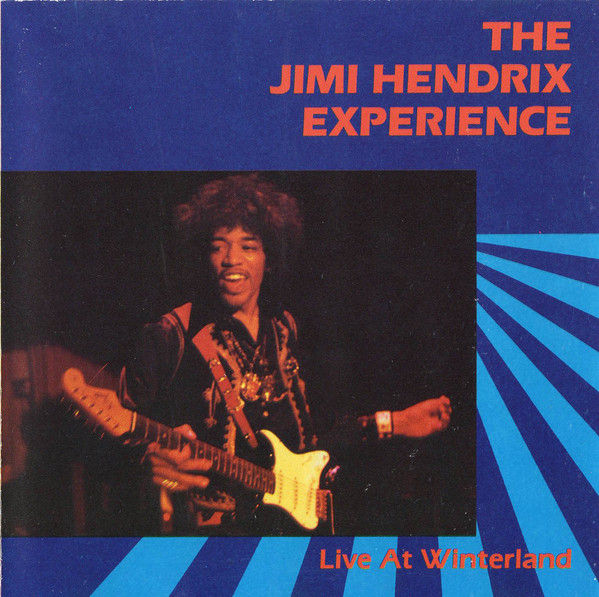

How Jimi Hendrix got the anthem right

When Jimi Hendrix deconstructed—that is to say, obliterated—our national anthem, he didn’t catch a lot of flak, which seems surprising in 2020. By strange—or fitting—coincidence, Francis Scott Key composed “The Star-Spangled Banner” on September 14, 1814, with Hendrix dying fifty years ago on the 18th of that same month, as if these two musicians were to forever be locked in sonic and ideological battle.

Taking a knee doesn’t remotely compete with Hendrix’s full-on pasting of Francis Scott Key’s ode to America, but I always felt Hendrix “got” the purpose of the anthem. It wasn’t a canticle of veneration—it was a reminder of a right to be heard.

The anthem, as Key wrote it, borders on proto-Muzak. The lyrics clunk, with forced transitions that could make Uncle Sam groan.

Hendrix turned an unwieldly composition into starshine made audible. The feedback, vibrato, and hammer-ons felt interplanetary, but we all know a gut punch when we experience one, no matter the form it takes. This was a gut punch—albeit the good kind.

The guitarist played the song prior to its well-known August 1969 Woodstock airing. An autumn 1968 rendition at San Francisco’s Winterland club was a kind of barrage-via-reminder that preexisting forms are malleable, sufficiently alive only when we treat them as such. Hendrix’s guitar strafed, but this was also the sound of a robust culture with reason for sanguinity.

Personally, I’ve never thought much about standing or kneeling for the anthem. Neither is this massive sign of respect nor disrespect. I see mild tribute either way.

You want to stand and honor what something represents to you, that’s fair. You want to honor values this country is built upon, in theory, by kneeling, that makes sense, too. The two supposed polarities really aren’t that much in opposition, which is probably a greater annoyance to people on antithetical sides of this issue— they’re not especially diametrical.

But Hendrix? He did something else, man. He ripped art from a kind of womb, which is patriotism of a different nature—the patriotism of the individual, something both Ben Franklin and Odysseus would get, as well as Hendrix, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, the cutters of their own paths.

That’s the spirit our anthem ought to represent, not indentured servitude to group think, to fear of opposition by a mob, or even concern that one’s own mob won’t be strong enough to countervail an advancing horde.

As George Orwell noted, the British excel at individuality, which is one reason he believed they were invulnerable to fascism. In 1966, Hendrix was of the opinion that he’d first have to go to England to later make it in the States, and so it came to pass. A couple years later, he dialed in on our anthem as a means to create a sonic statement about our greatest liberties, almost as if challenging his listeners—then and now—to be path-cutters themselves.

Hendrix wasn’t a guy who did half-measures, and that he’s never really been attacked for his take on the anthem speaks to the power of the art he made from it, art being arguably the purest representation of the individual spirit.

This, his guitar seemed to say, is how the tune ought to sound, because that’s how it sounds to the dogged individual I am.

That’s the point of the anthem—that you can make it your own via your inviolable individuality, your courage, your character, and, in some cases, like Hendrix’s, your chops. Hendrix didn’t so much as get away with something as he had something to teach us with his “Star-Spangled Banner.” A group has a sort of low-level lambency, but the individual is the real beacon.

Comments