You're down

- Colin Fleming

- Mar 19, 2019

- 15 min read

Tuesday 3/19/19

I awoke, I cried, I vomited. I vomited so hard that I popped some blood vessels around my eyes. Then I made coffee, while simultaneously preparing two mugs of tea. Both go in the microwave together and get time cooked for four minutes. "Time cooked." Like it's a food preparation technique. Baked, broiled, boiled, time cooked. I've been time cooked. I looked at Tinder. Some hot twenty-five-year-old arty grad student wants to fuck me. That's common. I look good in the photos after the years of not drinking and working out. My profile write-up is what you'd expect from me using my words. Unique, smart, funny, some edge. I'll probably have no interest in her. I can't do anything half-assed. I can't look to be involved with someone for this exclusive purpose, and not others. I'm going to be alone. Maybe forever. But I'm certainly going to be alone for this period of my life. No one is strong enough to join up for what this is right now. How could they even understand? No one is going to face this with me. Be by my side, believe. Wait. Help. As I take on worlds. They are not. I don't think there is someone that strong and that brilliant and that dynamic. I'd love to be wrong. And I think there are less special people with each passing year.

It's like being good enough to be in the Big Leagues. Then your skills erode. Then you finish your career in the minors. Then you're out of baseball and on your couch. (A couch is such an extreme luxury item to me right now. I can barely imagine being able to own a couch and have space in the place I lived to put it and sit on it.) Humans are like that now. Selves and brains erode. Then you dip back into the lower leagues. Then you can't even play there. Then you're on your couch. I'm going to toggle a bit right now and formally compose as I write this, just to feel a little more activity, make my blood circulate better. If I get to where I am trying to go, if I have changed the world, if I have killed off this industry and replaced it with something better and have gotten people reading again, and I have the recognition I deserve, and the money I merit, I will have more opportunities to meet whom that elusive person may be. And I will have to lie to myself in all probability that if she met me now--which, in this scenario, means in my past--she would have joined up and walked alongside this hardest part of the journey with me.

But I think that will be a lie I'll have to tell myself and try to accept, or something I should not think about, and let the past be the past, rather than a hypothetical. I am not sure either if there is anyone out there possessed of a mind that could interest me for two minutes, let alone enough for us to share a life. I used to think that Picasso was so much better at this, that he could find some attractive woman and he'd make it work with her. Sure, he had to go through a lot of them, but he always had some one. He didn't need anyone brilliant. But he was with brilliant people. I've come to learn that. There were enough of them that enough came into his orbit. Maybe it had to do with the fact that he was by then known as Picasso, art titan. Maybe he had to tell himself--lie to himself--that if he met one of them when he couldn't afford an egg they would have joined up to his cause. But it is much easier to join up to the cause of a young artist whose work has not been seen yet, than an artist whose work has been seen by millions who is viewed as the ultimate enemy of an entire industry who must be suppressed and abolished.

I don't vomit physically to start every day. But it was seven years ago this morning, on March 19, 2012, that the person who was my wife sent me an email saying I would never hear from her again--no explanation--and that I would hear from her lawyer, who turned out to be no less than two lawyers. My entire life was in her hands, from my trust, to my finances, such as they were. We had just gotten a house. She made not one comment--not a single one, not in conversation, not in email, not through a third party--expressing anything about what she did not want. She had been married before. She was going through a divorce when I met her. She said that that man tried to murder her. Tried to make her go off a road by loosening the tire on her car. She paid him six figures in alimony. He didn't work. He played video games at home. Said he was going to be a rock star. She said that he enslaved her. I believed it all from her. She sometimes kept a rolling pin in her bed, in case he came to murder her. I realize now that he probably didn't give her a second thought, save beyond that he knew someone evil and crazy who messed up his life. She went to Cornell. She worked at Harvard. I found out four years later she was having an affair.

If you read this journal, you might wonder how I got to be like this. (That sounds incriminating, doesn't it? Like something Peter Cushing would say to a priest who has come to visit him in his cell before execution for his crimes in a Hammer horror film, and he wants to explain his misdeeds, rather than be expiated for them.) I don't mean driven, I don't mean the genius, I don't mean as someone who set out almost from his earliest thoughts to realize what he had within him and legitimately alter how the world can work. Those things were always there. And I was always productive. If you compare my rate of output to other writers in, say, 2010, you'd have to go back to Fitzgerald's time to find anyone who produced at my rate. I'm talking sheer word count. I'm not talking number of novels, because with all I had to do, and have had to do since, this has been a time in my life when I can't do a lot of novels. Rather, I can do them. I will. But I have not had freedom of movement, for various reasons. Money. Then, of course, there was the blacklist. I could finish the best novel ever written today. When I have that first finished novel, it will be the best novel written. If you read my work, and you read these pages, I doubt you doubt it. You may even expect it. Or you may think, "that would not surprise me." Were the god of reality to tap you on the shoulder and say a word as to what this newly finished book was, qualitatively, you would not express shock. You'd find their commendation congruous with credibility and expectation. But if I have that novel here on March 19, 2019, there is no publisher who will put it out. There is not a single agent in America who will represent the evil Fleming. If by some miracle some shitty, small press that won't even put books in bookstores, and doesn't even do a print run--that is, the book is "print on demand," so it doesn't exist until you order it on Amazon, then they glue one together--puts it out, no one will see it. Kirkus and Publishers Weekly have a rule not to review my work. Greg Cowles at The New York Times Book Review--for whom I used to work, and someone I once bought lunch for--and a colleague of his--has instigated a policy there that no Fleming books will be reviewed, and he will also not be allowed to write about books. There will be no words on lit biz blogs, no awards, no "check out these fifty books coming out in February" citations, no excerpts will run. Because this is the most hated person in publishing. Not because they did what Lorin Stein allegedly did and anally raped people on his work desk. Nothing like that. But because of genius, effort, expertise, productivity. And being a self-made, good-looking white male. Who didn't go to Yale, who didn't go to Iowa, who can do in five minutes what none of these people can do if you gave them a million lifetimes. The true leading intellectual, who is also a normal person. Those are my crimes. I have never socially interacted with any of these people. I have never been on a single date with a person in publishing. I can't be bought, I can't be sold. Which probably makes me sound like a rebel, but as anyone who reads my work knows, who knows from my radio appearances, who knows from this journal, I am an ingratiator. I'm not here to write recheche work you can't understand. I'm here to connect with you. I am, morally, my own person. But a person of the people who can give so much to the world. I have never traded a favor, and the smartest person here is also the hardest working. And it's not remotely close on either score. And so, the hate pours in. I could scoop together that novel in a month. But even if there was not the hate, you have the insistence that someone right now possess the right genitalia, be the right skin color. I don't have those. Then they want you to write regurgitated MFA-isms that no one on earth cares about, which looks like other pablum that no one on earth cares about. A pen name, even if I wished to start all over, vacating an enormous--I mean, it's comical--amount of achievements would not bale me out of this situation. The writing would still be too good, too fresh, too enjoyable, too meaningful, too impactful to lives, and they don't want writing like that. I don't think they can even understand what writing like that is now. I think they've lived with lies so long that they have no clue about most things that involve a measure of perspective. It would also still be replete with truth, and these people hate truth, because they hate reality. A glimmer of both sends them to the meds and the therapist. To their cronies who help in the muting of the truth's knock--bang, bang, bang--at their doors. The cronies like cotton balls in the ears, scales over the eyes. The perpetual attempt to mute and blur. To be dumb and blind. Then you say that Lydia Davis is a good writer. And all your shitty writer friends, who don't have a mica-sliver of ability between them. Bang bang bang.

Everything changed for me on March 19, 2012. Some of what happened--and it's a very small part--is what is detailed here in an essay I wrote. And, for a time, I thought that 2012 would be the worst life could be for me. I didn't realize, then, that each year following, would become far worse. Exponentially worse. But they did, largely because of who I became. As I remarked, I was always productive. But as I wrote those millions of words to the person who was then my wife, and I wrote sixty magazine pieces, and I wrote three books simultaneously, more or less, in mere months, in Dark March, Anglerfish Comedy Troupe, and Buried on the Beaches, I changed at my core in terms of what I could do and how readily it could come to me, and the pace with which I could do it. While only improving as an artist and writer, in terms of what the result of each and every endeavor would be. Up until then, I felt like I could hang with Melville, Dickens. Name who you want. But it was at that point that I knew I was going beyond them. I was the test pilot, so far as artists go, who was also determined to return home. Not use my skills to die for some noble cause, if it came to that.

As I got better, faster, I tried harder. When ten amazing achievements produced no results, or, often, made things far worse--the hate, the envy, the "Not on my watch is this guy getting another great thing if I can help it, and hey, I can help it here, fuck him, I have control over these pages"--I tried for more and achieved more. When writing the best stuff wasn't enough, I became the best on the radio. When writing all of the fiction wasn't enough, and on sports, and on every form of art, I started lighting it up with op-eds. I said things that no one else was saying in op-eds--which tend to be super-safe, so that there is no vexation for anyone, thus no possible outcry, thus no digital mobs, which venues want because advertisers don't want there to be any outcry; they want a nice arid sterility--for which there was no blowback at the same time, because I write in such a way that both starts and concludes the conversation. Do this kind of fiction, do its opposite. Write on Singer Sargent for The New Criterion, write on Sidney Crosby for Sports Illustrated. Take your links, show them to people, as if to say (but not actually saying), "what the fuck more do you need to see?" which was as if to say, "we both know this has nothing to do with my work, the reason you are behaving like this. So you're just going to be corrupt and discriminatory then?" And they wouldn't respond, because they knew they were guilty as sin and I had them bang to rights. The optics were what they were, because the reality was what it was. It became more and more absurd as the achievements mounted, despite their attempts to bury me. And around I'd come again, with twelve new things from the last eighteen days, and three great ideas, or the story better than any they were publishing, and again, there would be nothing.

As I achieved more, there was more nothing. My friends were excited around this time last year when a story was coming out in Harper's. And I was glad I achieved that. It was a good fit, my work with them. And I dealt with some serious assholes there over the years who had finally left. But I knew it was going to be awful. I knew how much more hate and envy there would be after. And it was going to be really hard to place even one fiction masterpiece, for free, after the lit bizzers saw my story there. And so it came to pass. I wonder if there's something I can achieve that will flip the switch, or the bigger the achievement, the more hate there will simply be, the pattern--that is actually worse than one born of hell; it's like there's a torture zone past hell--persisting. I sort of believe I could win six Pulitzers, be crowned art king of the world, make millions, do films, TV, have a radio show, speak at places like Symphony Hall, which David Sedaris does, which seems a low bar, and there wouldn't be an agent in America who would touch me (nor would I go with an agent, at this point, for many reasons), or a shitty literary magazine that would take a story for no payment and a contributor copy. I think these people are that pathological. I know someone who says I think this primarily, in terms of the persisting of the themes and trends, because I am battered all day every day such that I can see no positive outcomes as possible, nor even imaginable, often, and that is perhaps true. This person could be right. They believe that something will happen where hands will be forced. And then things will go very fast, from sitting here working my ass off on a morning like this, to in my house and beyond in two weeks. But they have little to say in terms of what that thing could be. Or will be, to give them the benefit of their preferred conjugation.

I awoke at 7:09 this AM. I was seated at this desk by 7:38. I remember in 2012, I had slept later. I had fallen asleep with Downton Abbey on. It was after 8 when I received that email. It is 9:48 now. As I have been writing this, I have been writing that aforementioned new personal essay, "You're Up, You're Down, You're Up." I am composing at a high level. I am going to walk to Charlestown and climb now. I have to be funny and entertaining on the radio later. These are the first 1000 words of the essay.

Here in the Great Age of Victimization, where remarking that something baneful was done to your person in terms often outpacing the severity of your experiences, in hopes to fill the voids within, I have noticed a rise in some forms of clichés, and a downturn in several word-based palliatives that people used to offer the truly wounded.

For instance, in the camp of the former, we have the idea that you should personalize truth, as in, say what yours is—overlooking, or attempting to countervail the reality, that truth has no possessor. It’s not owned. It’s not cajoled. It’s not managed. At best, it is accepted, and it is dealt with. If you’re a Kinks fan, you might know a song by Ray Davies called “Have a Cuppa Tea,” from their 1971 album, Muswell Hillbillies, which is less about a mild stimulant, and more about something connective, though we now often court disconnection, when a salient point of view, is athwart the model we have built for what we wish to believe, and we balk, we become angry, we dismiss. It’s a jaunty song. You could busk it at a subway station. In olden times, someone might hear it and nod and say “verily.” Or “aye.” Or, now, “fuck yes.” Were they a wise individual.

Whatever the situation, whatever the race or creed

Tea knows no segregation, no class nor pedigree

It knows no motivations, no sect or organization

It knows no one religion

Nor political belief.

That connective something, that life tea, as it were, is the truth, regarding which someone would have once deployed banal, but accurate, wisdom in stating that it would set us free.

It’s more that it pinions us now, requiring the recasting of the various players in the dramas that our our lives—our existences, more like it, as I increasingly think of them—so that they fit better in our personalized narratives of “our truths,” where the corpulent fellow plays someone meant to be thin, the hero is the villain, the sea battle takes place in a little below-ground puddle, and damn anyone else who dumps tea on the stylized, personalized endeavor meant for an audience of one—the person who did the overhauling—and the friends who maybe aren’t such very great friends who enable the process, so that their similar one might be enabled in turn.

I think that’s why people don’t say much anymore that from great loss can come great surges of strength. We claim we don’t have time, we are harried, when we are harried, we don’t have great energy, when we have neither time nor energy, we seek shortcuts, and anything that positively moves us along in life is the mental and spiritual version of taking the long way ‘round.

The long way can, ironically—and this is a great secret that few seem to be in on—be faster, because you move at a greater clip, once your legs are under you, than you often do in the shortcut, which no one points out to you is lined with alligators sticking their mugs out of the sides of the narrow cutting that is this swamp as you go, keen to chomp into your hips and your calves, and there is quicksand everywhere, like this swamp is managed by a perverse grounds crew that dumps in sticky ooze and fast-binding agents, with a devotion to duty standardly reserved for getting every last blade of grass in equal-sized serried ranks at Fenway before a World Series game.

Then there are the clichés serving as directives in ordering us to believe what anyone—well, not anyone anyone, but the right kind of anyone—tells us befell them. I don’t do this. If you say something happened to you, I am not going to believe it. I am not going to disbelieve it, though my initial lean will be in that direction. I am going to think, “that’s what they say, but I don’t know them, and they could have all kinds of reason for wanting to say that, especially now.”

Do I expect you to believe what I might tell you happened to me, in an essay like this? I think I would, because of how I’d convey it to you, but I don’t want to tell you what happened to me. This is neither the time, nor the place. I remember we were reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was in high school. I’d read it as a kid, thinking it was like a fairy tale, not a sci-fi morality novel, which is also what it is, and how this teacher talked about it.

Mary Shelley made some vague reference early on as to processes that put life back into the Creature. (I always call him the Creature, not the Monster. We don’t wish to victim blame.) She didn’t elucidate those processes, and the teacher asked us why that was the case.

Someone raised her hand, and and when called on she volunteered, “Because she didn’t know.” That was it. Life had come back into something that was dead, and even Mary Shelley, great writer that she was, couldn’t provide us with a believable reason, so she left it out. Glossed over. Skillfully, but glossed over all the same. She left out the death-based part to move forward with the life. Something with death roots, anyway.

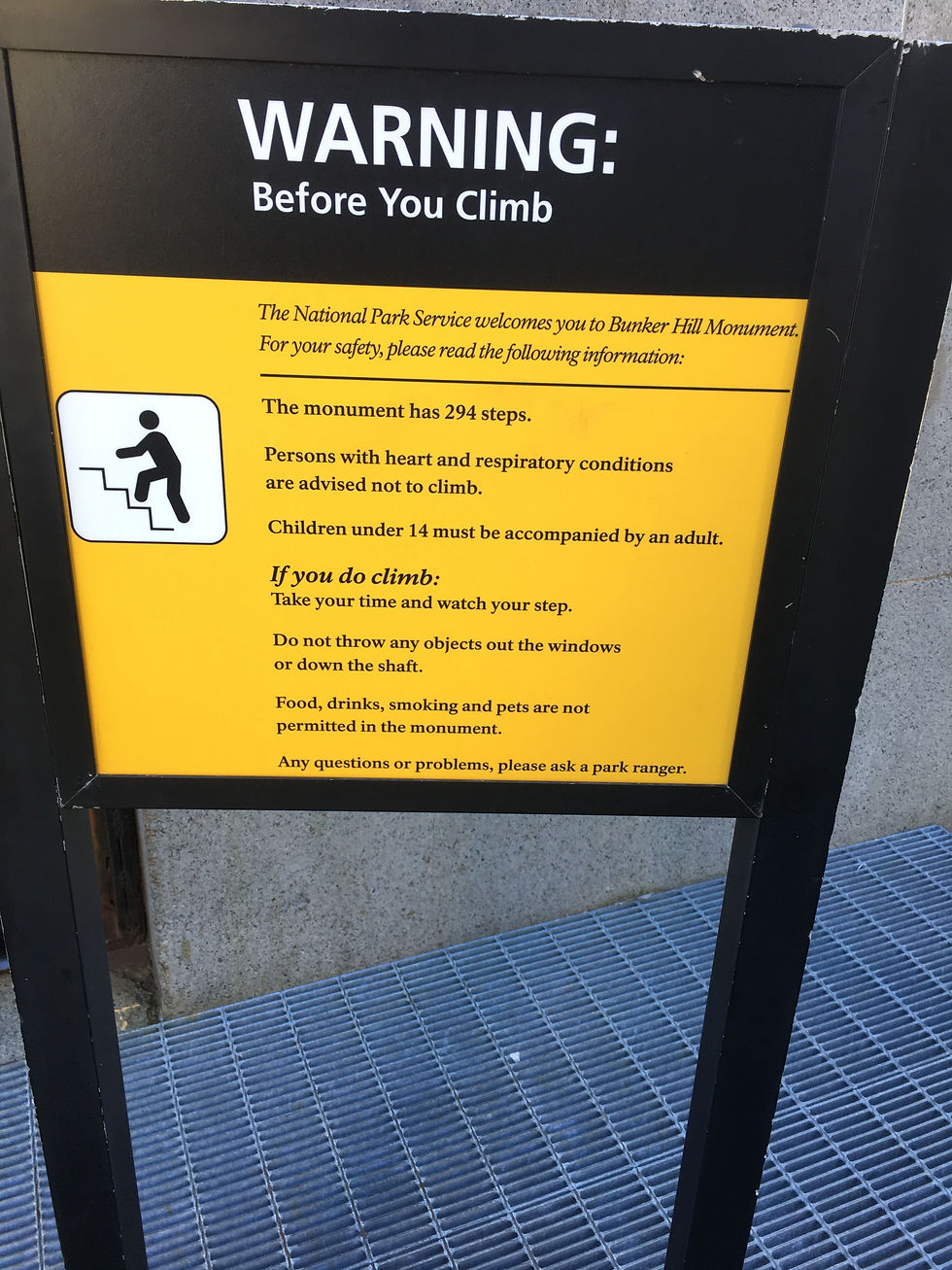

There is another British band you probably don’t know—they didn’t make a huge mark in the States, unfortunately—called the Music, whose 2002 single, “Take the Long Road and Walk It” plays at times like an anthem in my head. It’s not strictly about walking, and is more about remaining animated. In motion, that is. Not a perpetual cartoon. I would like to tell you about one method I use to achieve this ends, on which I can elucidate in detail. I don’t ask you to believe—not here, anyway—what happened to me. I am simply going to tell you one thing I do. It involves getting vertical many times a day, many times a week, many times a year. Inside of an obelisk that commemorates a very famous battle in this country’s history, which is why many tourists come to it every day. It connotes something different to me. But let me just tell you about my climbs, as I refer to them.

The long way up, as it were.

Comments