Books I could and should write books about

- Colin Fleming

- May 28, 2024

- 4 min read

Tuesday 5/28/24

These are books that I want to write books about. I want to talk about how they work, how they came to be, how they function, their structure, what they offer readers, their worlds, their value, the techniques, and open all of that up to everyone. People who have read one of these books, people who haven't heard of a particular book, people who read a lot, people who don't read much, as in keeping with one of my core maxims: No reader left behind. I was thinking like a series for a side of the bookshelf. Books 30,000 in length. And these books, of course, would contain my own insight on writing and writing well. These are the books I'd like to do books about:

William Sloane's To Walk the Night (1937).

This is my favorite book. I've read it at least fifty times. It's also the best novel I've read. It belongs to no category but is in part horror, sci-fi, mystery, locked room mystery, family saga, fraternal tale, sports book, college lit. Also the ultimate book of autumn.

F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night (1934).

His best novel, and a flawed one, being too reliant on his own life, but with passages of near-perfect prose. He was in a very different than when he wrote his other novels. 1930s Fitzgerald was a very different proposition than 1920s Fitzgerald. This is akin to his White Album.

Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1767).

It has always amused me--and also made a certain amount of sense--that Sterne wrote this to make money. That was his goal. A commercial hit. I love that. He went for it. Didn't think, "Oh, you can't do that," but rather, "The fuck I can't, motherfucker." Truly funny. More true to life than anyone else has ever thought, too. Orson Welles said that the best bits in his films were the bits that didn't advance the plot, and the studios wanted everything to advance the plot. There's an emotional plot to things, too, though, and a psychological plot. People err in thinking that plot is physical or physical action and that alone.

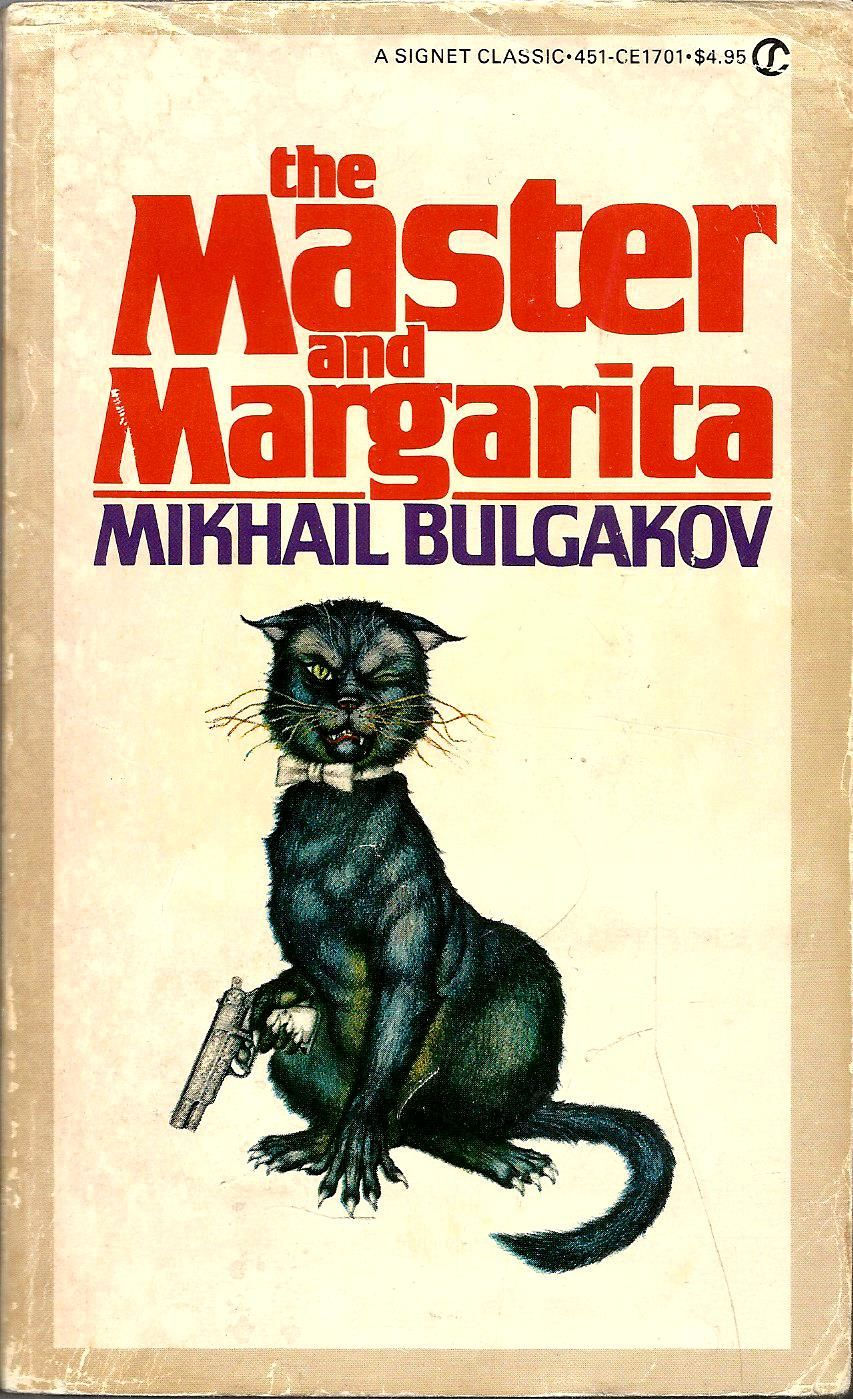

Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita (1967)

I first read this novel in eleventh grade for school, though I was the only one in the class who did so. Why? The teacher--who was this young guy who wanted to push students on, and sort of taught his own way, with his own style--assigned a different book to every kid in the class that he thought befitting them. You were to read it, then write about it. Well, for me he selected The Master and Margarita, which may or may not say something about how I came across to a teacher at the age of seventeen. It's a palimpsest novel. You have Pontius Pilate, a vodka drinking cat, and also this love story that could have come out of a 1950s rock and roll ballad.

Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897).

Postmodernism, though no one has looked at it that way. It's a technological novel. A composite novel. Less an epistolary novel than a collage novel. Stoker wrote it to make a different kind of name for himself. He wanted to be seen as worthy on his own, not just this person who did things for Henry Irving. His research was evidence of his sincerity in the endeavor, but so was the style. Stoker wouldn't write this way anywhere else. His other work is stodgy, with this throwback style. Dracula took us into a more modern--yes, that's a thing--century.

Arthur Conan Doyle's The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902).

It's a nature book. A book of place. Environment as character.

Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White (1860).

Sharp, witty, funny--very funny at times--and a potboiling Gothic, and there isn't much we can say that about. Has this fantastic, "No way!" moment in the middle of it that will get you every time. A detective novel that isn't regarded as such, but which makes the astute point that we're all detectives, really. People seeing the date of the book's publication and not having read it would, in reading it, be taken aback, I think, to see how current, if you will, the prose is. They'd be apt to believe they had some edition with updated language. Populism and art meet.

M.R. James's Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904).

James's first book of ghost stories, all of which were written to be read aloud, which makes for a different sort of book. James is a curious case--a non-writer who wrote very well. A reader who wrote. He ordered the stories by date of composition. So he wasn't thinking like a writer would. These are, as I said recently, inside-the-house campfire stories. They're also stories to be read over the course of a lifetime--say, once a year, if one wishes. You wouldn't get bored or be like, "There's no point, I know how that's going to work out." And that's a very important thing with ghost stories, and, frankly, all writing in my view if its succeeding.

Comments